Disco Down

How a forgotten short story carried me from heartbreak to a place on the podium

Last month, I received the harshest feedback I’ve had in years on a piece of academic writing I’d spent three months working on. It wounded me more than I expected. I cried, felt foolish, and closed my laptop with that hollow sense of why do I bother?

And then — because life has a strange sense of timing — I saw an advert for the Jesmond Library Creative Writing Competition. Theme: roots. At first I dismissed it. I’m not a nature writer; what on earth did I have to say about roots? But the idea wouldn’t leave me alone. I started thinking. Not about trees or gardens, but about the roots of home, the roots of the life my family have grown together, the roots of who I was in those early months after my son’s 123-day NICU stay.

Somewhere in that tangle, I remembered a short story I’d written years ago, back when it was just me and my six-month-old boy at home, him still on oxygen, still so small and not showing any sign of knowing who I was. I dug it out, revisited the theme, and reshaped it. Then I pressed send. I went to bed with a quiet sense of having done something for myself. An achievement.

The prize giving was last night. I almost didn’t go.

I am tired. My son is not sleeping, again. But a good friend drove me there, parked the car with ease, and sat by my side as we listened to other people’s stories. The children’s entries were beautiful (I cried a bit), the poetry carried me away to distant sounds and smells, and I felt myself relax, remembering the pleasure of writing for its own sake.

And then, to my shock, I came second place in the short story category.

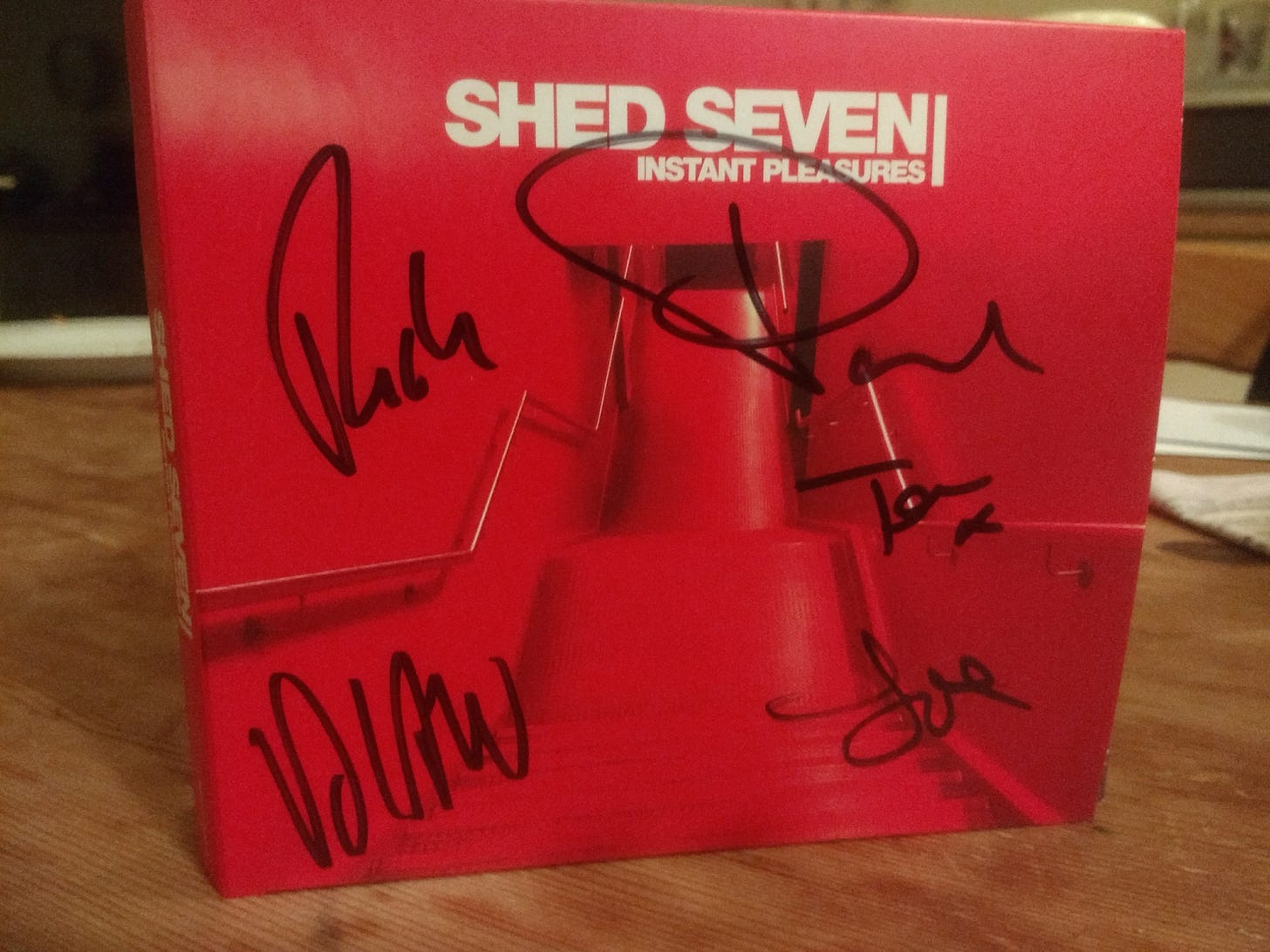

What follows below is the piece I entered and read at the prize giving: Disco Down. As I said on the night, it’s a love story to the lead singer of Shed Seven, Rick Witter. And also to my son of course - but mostly Rick and his maracas.

Here it is.

Disco Down

It’s mid-week and I am on my own with my six-month-old son Blake. I have dragged his baby bouncer chair into the kitchen, bit by bit, scratching the floorboards, stopping to make sure his oxygen tank comes with us.

We’re in the kitchen because it is a change from the living room. I stand with the small of my back pressing into the kitchen counter. My arms are folded, and I’m wondering what to do now.

As usual Blake is unfazed by this interlude. He spent the first 123 days of his life in neonatal intensive care – four months of machines and monitors and pain-faced doctors. Despite remaining by his side, day and night, Blake shows no sign of knowing who I am, or if I even exist at all. His gaze never meets mine.

My husband Mark has installed Smart Hubs throughout the house. The Hub in the living room displays a carousel of recent and not-so-recent photos. And it tells the time. But mostly, Mark and I enjoy asking it to live-stream the doorbell camera we’ve stationed outside, so that we can watch for delivery drivers appearing with takeaways. We make audible groans of disappointment when the promising glare of headlamps creep on screen, only to turn out to be a neighbour pulling into their drive.

There’s a Smart Hub by the microwave in the kitchen too. I ask it to play a radio station dedicated to the sounds of the 1990s. It’s mostly Britpop.

‘Only three hours until Daddy comes home!’ I say to Blake.

I imagine the house listening in, holding our routines in its walls. After months of nothing but hospital walls, ordinary feels like a luxury. Even here – between the cupboards and the counter tops – we are planting something steady, something that belongs to us.

Blake’s head is turned to the left. The cannula feeding oxygen into his nose is stuck to his cheeks with tape I have cut into the shape of clouds. His eyes are huge, much larger than seems right for his small body. This gives him a permanent look of shock or disbelief.

I have rolled up the sleeves on his baby grow, because, despite it being the right size for his age, his body swims inside. His fingers curl tight into a ball and let go, repeatedly, like he’s working out what they are.

In the last few days, a flicker of a smile has danced across Blake’s face. His heavy head lolls forward hard, but then he lifts it, stops, and one side of his mouth curls upward. It’s blink-and-you-miss-it stuff. But there’s definitely something. A seed of an expression, pushing its way through.

I don’t know what compels me do it, but as the strains of Shed Seven’s ‘Disco Down’ pumps out of the Smart Hub, I open one of the kitchen cupboards and grab a Kilner jar half-filled with dried penne pasta. I start shaking it, in time to the music. The pasta bounces around the jar, making a high click, click sound.

Blake is mesmerised. He looks directly at the container, and his tongue starts to peek out. I shake and sing along. There’s a twinkle on his lips. I shake the jar from side to side and twirl in a circle. When my eyes come back to meet Blake’s face, his cheeks are high. He is smiling.

He pushes out his chest and makes a wheezing sound.

He is laughing.

‘Blake, this is Shed Seven!’ I shout over the music.

Lead singer Rick Witter sings about records spinning around forever, the memories of nights spent dancing.

‘Shed Seven are from York!’ I yell.

Rick’s going to burn the disco down.

‘Mummy used to get their albums out of the library after school. Mummy had this song on a tape!’

I keep shaking the pasta like Rick Witter shook his maracas in 1998 until, eventually, like my own wild nights out on the town, before I became a mother, the song fades away.

But Blake’s laughter doesn’t. It stays. It plants itself deep inside me, anchoring me, anchoring us both. The music ends, but something else is just beginning: the sound of a boy learning how to smile in his house, putting down roots of his own.

What an inspiring journey, it's truly amazing how creativity can help us proces such deep experiences and reconnect with our roots.

Elaine you are such a beautiful writer. 🧡